Bag Props on California’s ballot: Yes on 67, No on 65

By: Jennie Romer On September 30, 2014 Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 270, making California the first state in the U.S. to adopt a statewide plastic bag law. Later that day, representatives of the American Progressive Bag Alliance (a group of American plastic bag manufacturers and related companies) submitted paperwork to California's Attorney General for a statewide referendum seeking to undo the statewide bag law and require approval by voters. The referendum put implementation of California's statewide bag law on hold pending the outcome of a November 8, 2016 ballot proposition.

Background on the Creation of Local California Bag Laws

Passage of California's statewide plastic bag law was the culmination of years of grassroots community advocacy focusing on passing local bag laws, which faced strong opposition from the plastic bag manufacturing industry. In 2007 San Francisco was the first City in the U.S. to pass a plastic bag ban. That same year, industry groups (namely Save the Plastic Bag Coalition) began filing numerous lawsuits against municipalities in California that adopted similar legislation. The lawsuits alleged that the environmental impacts of paper bags might be worse than those of plastic bags and claimed that expensive Environmental Impact Reports were required pursuant to California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) for each municipality considering adopting a plastic bag ban.

SPBC's claim relied primarily on Life Cycle Assessment studies comparing plastic versus paper and reusable bags according to various environmental parameters. The CEQA lawsuit against Manhattan Beach went all of the way to the Supreme Court of California, which found that a full EIR wasn't required for Manhattan Beach's ordinance. At that time California's plastic bag recycling law preempted municipalities from charging for plastic bags, but that preemption against fees did not apply to paper bags. Municipalities began adopting "second generation" plastic bag bans that mandated a small charge for paper bags, which helped counter the argument that paper could be worse than plastic because the laws were designed to bring about an overall reduction in carryout bag use.

The second generation plastic bag bans were incredibly successful in reducing overall carryout bag consumption by changing consumer behavior; customers reacted to the small 5-10 cent charge for paper bags by reducing their consumption more significantly than expected. In San Jose, California the ban on thin plastic bags and 10-cent charge for paper bags led to an increase in customers bringing their own reusable bag use from 4% before the law to 62% after and at the same time the average number of single-use bags used per customer decreased from 3 bags to 0.3 bags.

Municipalities generally don't have the authority to collect taxes unless specifically authorized by the state. To get around this, the entirety of the money collected as part of California's local second generation plastic bag bans stays with the retailer. Nonetheless, the largest plastic bag manufacturer in the U.S., Hilex Poly (filed under the name of lead plaintiff Lee Schmeer, a Hilex Poly employee, as well as itself), sued one of the first municipalities to add a charge for paper: LA County. Hilex argued that even though the entire amount of the charge stayed with the retailer and no money went to the government the charge was still a tax. A previous voter proposition sponsored by industry groups had broadened the definition of tax under the California constitution to include certain regulatory fees but, because all of the money stayed with the retailer, Hilex's argument ultimately lost at the California Court of Appeals and LA County's paper bag fee remained in effect.

The next hurdle for plastic bag ordinance structure was the reusable bag loophole: some retailers had begun giving away thicker plastic bags (over 2.25 mils thick) that qualified as "reusable" for free. San Francisco closed this loophole by adopting new legislation making the 10-cent checkout bag charge for paper also apply to reusable bags so that no carryout bags would be given away for free. This structure further insulated the San Francisco's new ordinance from CEQA claims (SPBC sued, San Francisco won).

California cities and counties served as legislative laboratories for the creation of carryout bag laws with a state-of-the-art structure that stands up to legal challenges and has the greatest impact on reducing the impacts of carryout bags. The structure of California's statewide bag law (SB 270) follows that of most of the 151 local bag ordinances adopted by cities and counties in California, including San Francisco: a ban on thin plastic bags and minimum 10-cent charge for paper and reusable bags, and the entire amount of the charge stays with the retailer.

How the Statewide Bag Referendum Happened

As mentioned above, the initial paperwork for the referendum was filed on the same day that SB 270 was signed into law. On October 14, 2014 the referendum against SB 270 entered circulation, meaning that the referendum's proponent Doyle L. Johnson had 90 days to "collect signatures of 504,760 registered voters – the number equal to five percent of the total votes cast for governor in the 2010 gubernatorial election – in order to qualify it for the statewide ballot." (Doyle is the attorney that filed the initial paperwork and is financially sponsored by American Progressive Bag Alliance.) The referendum aimed to overturn all aspects of SB 270 except one subdivision that plastic bag manufacturers found favorable: a provision that would create a two million dollar Recycling Market Development Revolving Loan Subaccount that provide loans for manufacture and recycling of plastic reusable grocery bags that use recycled content. This first initiative would become Prop 67.

Environmental advocates that had been advocates for the state's plastic bag law filed a complaint with the California Secretary of State calling for an investigation of the signature gathering by the law's opponents, citing numerous examples of deceptive signature gathering. The complaint asserted that voters were urged to sign petitions to “save” the statewide plastic bag law rather than stating the true intent of the referendum: overturning the law. Examples included a Craiglist job posting for signature gatherers stating "It is basically to reverse the ban, but the way you pitch is to vote on it whether you want it or not."

On October 2, 2015 Doyle L. Johnson and Kurt Oneto submitted a letter requesting a title and summary for a ballot initiative requiring that any bag fee collected must be directed to a state fund. This second initiative would become Prop 65.

Ultimately both propositions qualified for the November 8, 2016 ballot. Sponsors of Prop 67 spent a total of $2,911,945.89 to collect the 504,760 valid signatures required to put that measure before voters. Sponsors of Prop 65 spent an additional $2,137,992.45 to collect the 365,880 valid signatures required to put that measure before voters.

Propositions: Yes on 67 (saves the bag law), No on 65 (distraction)

Prop 67 is titled California Plastic Bag Ban Veto Referendum. A yes vote on Prop 67 upholds the statewide bag law.

Prop 65 is titled Dedication of Revenue from Disposable Bag Sales to Wildlife Conservation Fund. At first glance Proposition 65 may sound reasonable, but it is deceptive. The sole purpose of Prop 65 is to confuse voters and serve the interests of plastic bag manufacturers in protecting an unregulated marketplace for their product. Prop 65 drives a plastic vs. paper narrative rather than a more comprehensive law to reduce single-use bag consumption overall, which is achieved by Yes on 67.

Environmental groups in California have endorsed Prop 67 but not 65. Environmental groups support the structure of SB 270, which is based on local laws that allow the retailer to retain the full amount of the 10-cent charge. This mechanism was necessary for local laws to pass constitutional muster (see above) and charging for paper and reusable bags has led to a change in consumer behavior in favor of customers bringing their own bags. Additionally, the carryout bags that SB 270 allows to be sold for a minimum of 10 cents (paper bags with 40% post-consumer recycled content and reusable bags) cost roughly that amount at wholesale, if not more, so retailers will not be receiving a windfall. Plastic bag manufacturers, led by the APBA, have invested millions on creating this false pseudo-environmental narrative of "grocers get richer" in hopes that it will sway California voters.

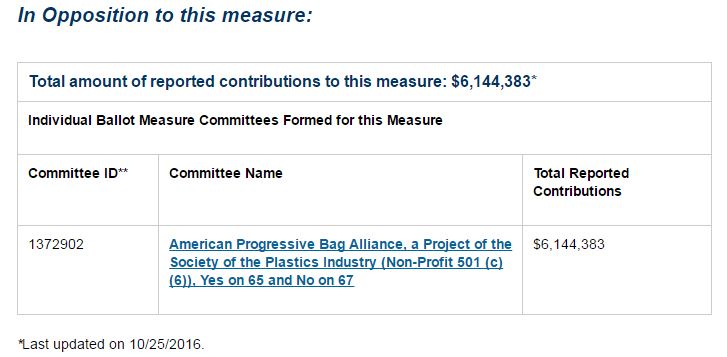

On the Secretary of State's website, funding for the campaign against 67 and in favor of 65 campaigns is combined under one Committee ID number and have reported a total of $6,144,383 in contributions. The biggest contributor to the propositions South Carolina-based is Hilex Poly, the largest plastic bag manufacturer in the U.S. and the plaintiff in the above-mentioned lawsuit against LA County alleging unconstitutional taxation. Hilex Poly has contributed a total of $2,783,739 to date.

A Mercury News editorial endorsed Prop 67 and urged ". . . vote no on Proposition 65, one of the most disingenuous ballot measures in state history — and that’s saying something. The proposition requires that the money shoppers pay for paper bags in stores go into an environmental fund — but major environmental groups actively oppose it."

Vote Yes on Prop 67 and No on Prop 65 to save California's statewide bag law.